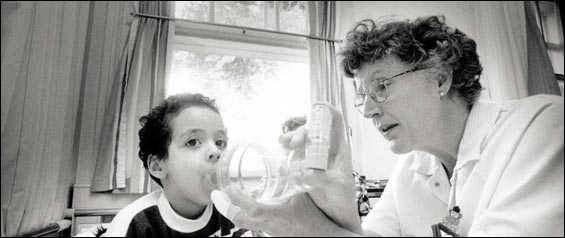

Kids with asthma could breathe easier

For weeks when I visited Bombay as a teenager, I'd awake at 2 a.m. and feel iron bands around my chest. I descended into an airless world where every wheezy breath was a struggle. I'd wake and cough violently near the window, bringing up thick, jelly-like sputum.

That was my first asthma attack, and the flare continued for weeks. It was like running a marathon every day while trying to breathe through a long straw. Unfortunately, no medications were available, so I accepted the fatigue and breathlessness.

Like me, millions of American children have suffered from asthma, and recently researchers have learned a lot about controlling it. But many children still continue to suffer as I once did -- without good reason. In 2002, the Centers for Disease Control reported 6 million children had asthma, and a quarter of them had ''activity limitations" as a result. The prevalence has increased by roughly 40 percent over the past two decades.

Effective treatment has been around for more than 10 years. Every few years since 1991, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has convened an expert panel representing 40 major medical associations, and has published a clear recipe to treat asthma. Affected children are supposed to have written plans, geared to the severity of their asthma.

Unfortunately, most children today don't get the right treatment because many people don't realize that asthma is actually two problems requiring separate therapy.

Children with persistent asthma need two medicines -- ''rescue" drugs only when urgently short-of-breath, and ''controllers" like Flovent or Singulair daily even when feeling fine.

The first problem in asthma is that the lungs are too twitchy. When an offending trigger -- for example, pet dander or house dust -- enters the lungs, tiny muscle fibers around the airways tighten up. This constriction makes it hard to move air; hence, the wheezing sound. Rescue drugs force these muscles to relax.

Rescue drugs treat attacks but don't prevent them, which is why controllers are needed. But in a 2000 study in Pediatrics, researchers from the University of Rochester found that only one in four children with asthma got them. This is an oversight since the second problem in asthma is that the tiny airways of the lungs, called bronchioles, are inflamed and swollen. Smoking and certain allergens may trigger this. Rescue drugs can't fix this problem; this isn't due to twitchy muscles, but controllers like inhaled steroids or other anti-inflammatory drugs can.

Controllers clearly prevent attacks and improve quality of life. According to the NHLBI's expert panel in 2002, ''strong evidence from clinical trials has established" that controllers lead to ''improvements in symptom scores and symptom frequency . . . and fewer urgent care visits or hospitalizations." (Last month's New England Journal of Medicine questioned whether controllers help adults with mild asthma, but this is a different study population than children with moderate or severe asthma.)

Why don't kids use controllers? According to a study in this month's Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine that included Boston-area doctors, only half gave written asthma plans, and only 40 percent prescribed controllers. A series of intensive seminars about the value of controllers showed no subsequent improvement in controller use, according to a followup evaluation.

At last week's annual Pediatrics Academic Society conference, Seattle-based researchers presented preliminary data on the use of computers during children's checkups to remind doctors to prescribe controllers. The result? Still, less than half of children with severe asthma got them.

Even when controllers are prescribed, according to a 2002 Pediatrics paper, half of parents don't give them -- perhaps due to misunderstanding or fear of side effects (however, these steroids are very different and far less toxic than anabolic steroids used by body builders). In another 2002 study, two out of three urban pharmacies didn't carry needed supplies to treat pediatric asthma due to ''low demand, trouble with reimbursement, and store policy."

The traditional model of managing patient care doesn't work well for complicated chronic problems like childhood asthma, many experts say. More creative and cost-efficient solutions are needed: A solution like providing a ''disease manager, " or nurse-specialist, who acts like an asthma coach for a roster of kids with asthma for a health plan.

This coach, offered by a growing number of health plans, regularly reviews a patient's history to ensure the right controllers are prescribed, coordinates with a doctor to arrange followup visits, and contacts families and doctors repeatedly to ensure that treatment is progressing according to guidelines. In a study this month, children in a similar program had two extra weeks without asthma symptoms per year, for very little cost. Yet, this sensible and highly effective system isn't offered to most children.

Another solution comes from the Inner City Asthma Study, which provided kids with asthma in seven major cities with comprehensive home-based allergen removal, including bedcovers, air filters, vacuum cleaners, and pest extermination. This intervention gave children an extra symptom-free day every two weeks. (Local families can call 617-534-5966 for information about allergen removal.)

Ideally, of course, asthma would be prevented completely. Recent data suggest that kids in day care, those with pets, and those exposed to house dust have lower risks of getting asthma, perhaps because such exposure makes their immune systems work better. But the studies are conflicting and, according to the New England Journal of Medicine, ''do not support a primary-prevention strategy based on the manipulation of exposure to allergens in early life."

Since nobody's found a good ounce of prevention, we should focus on getting kids their pound of cure.

Dr. Darshak Sanghavi, a

clinical fellow at Children's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, can be

reached at www.darshaksanghavi.com.

![]()