Baby Steps

Medical breakthroughs don't happen overnight. They come only after a few pioneering patients go first, sometimes at great risk. When Brian and Jennifer Deffaa learned their baby would be born with a damaged heart, they had a choice: accept the standard but imperfect fix or let doctors try a radical, unproven procedure. This is the story of one family's agonizing decision and the human cost of medical progress.

The first indication of a problem occurred in a small, darkened exam room at a clinic outside Los Angeles in the fall of 2003. Jennifer Deffaa lay back on the hospital bed and watched the computer screen. A 29-year-old occupational therapist, Jennifer had met her future husband, Brian, 32, at a Halloween party five years earlier, when she was in graduate school. She and her roommates dressed as the Spice Girls, and Brian Deffaa (he admitted that his costume was "utterly unappealing") came as a "Catholic schoolgirl field-hockey player." The two married after a yearlong courtship - Brian joked that it was largely spent overcoming her first impression of his costume - and Jennifer was now five months pregnant with their first child.

For nearly a year, Jennifer and Brian tried to conceive. Then a home pregnancy test came up positive. Jennifer gift-wrapped the test and hid it in the medicine cabinet with a note. That evening, she feigned a headache and asked for some aspirin. Brian found the package and note, which read, "We did it!" They were elated and, as a healthy young couple, didn't anticipate any problems.

Now five months pregnant, Jennifer watched as an obstetrician squirted warm jelly onto a wandlike probe and glided it over her belly. To the untrained eye, the resulting ultrasound images are snowy and unrecognizable, with tantalizing hints: Is that a finger, a leg, possibly a head? For a parent to see a child on the grainy screen requires imagination and a dose of quixotic faith.

|

|

While scanning the heart, the obstetrician paused. Beginning as a narrow, microscopic tube, the human heart begins beating within a few weeks of gestation. Soon, the tube loops and twists like a carnival balloon, and by five months, the cherry-sized structure should be almost fully formed, with four chambers, four valves, and its own blood supply. But the obstetrician noticed that the heart's main pumping chamber, the left ventricle, was very abnormal.

The jelly still warm on her abdomen, Jennifer lay half-dressed on the table when the obstetrician broke the bad news to the couple. "Your baby," he said, "has hypoplastic left heart syndrome, or HLHS. There is slim to no chance of survival." Devastated, the Deffaas didn't recall much of the later conversation. That Tuesday evening, says Jennifer, "we just held each other for hours and cried."

The next day, they drove to see a pediatric cardiologist in Los Angeles, who confirmed the diagnosis. The specialist said that even with treatment, the chance of survival was 50-50, and then he hinted at pregnancy termination. But that night, Brian, a marketing executive for an automaker, scoured the Internet and turned up websites suggesting that HLHS was less fatal. The Deffaas also told their extended family the diagnosis. Brian's mother remembered that her neighbor's son-in-law was a pediatric cardiologist, and he told them of a new treatment. Brian was directed to Dr. Wayne Tworetzky, a pediatric cardiologist at Children's Hospital in Boston. The Deffaas e-mailed the hospital on Thursday night, and Tworetzky called back with encouraging news. On Sunday, they got on a plane to Boston, where doctors were developing a radical heart procedure for patients still in the womb.

This is not the story of a child's miraculous cure, but a portrait of how medical techniques evolve. Contrary to popular belief, dramatic leaps don't typify medical progress. Rather, small gains are made when a few pioneering patients volunteer to go first - and sometimes suffer prolonged misery from procedures almost guaranteed to fail in their first attempts.

I was one of many physicians at Children's Hospital later involved in the care of Brian and Jennifer's baby, and I often struggle with the decision to try new technologies on tiny patients. Still early in my career - though a board-certified pediatrician, I've been training in pediatric cardiology for only two years - I've seen firsthand the heroic therapies that save children's lives today. Like many parents, I'd probably want the most cutting-edge treatment if either of my two young children were sick. Like many physicians, though, I also know that there's a learning curve; for us, practice makes perfect. Like no family before, the Deffaas made me consider the human cost of developing new therapies. Allowing children to undergo highly innovative and potentially disabling treatment represents a peculiar tradeoff. While the knowledge gained can help future patients, families play a sort of lottery where the winners might get a cure - but the losers can end up much worse off than where they started.

After the story of Brian and Jennifer's experience with the fetal heart procedure had unfolded, I couldn't help wondering: Did we all do the right thing?

Not so long ago, physicians intentionally kept parents like Brian and Jennifer in the dark. There was no "informed consent" procedure where doctors wrote out a new treatment's risks and benefits in detail; instead, as their children were wheeled away, parents simply had to assume their trust was well placed. The practice of pediatric cardiac surgery was no different. Doctors sometimes even kept pioneering work from supervisors and ethics boards, fearful they might be thwarted.

In 1938, Dr. Robert Gross at Children's Hospital in Boston performed the world's first heart surgery on a child by tying off an extra blood vessel that caused heart failure. Clandestinely, he did the procedure over the summer when his chief was away. Similar audaciousness was required in 1954, when Dr. C. Walton Lillehei at the University of Minnesota temporarily joined the blood vessels from a father's groin to a baby's chest - essentially using a father as a heart-lung machine for his baby - while he repaired a hole in the baby's heart. His critics, Lillehei later wrote, "were quick to point out that this proposed operation was the first in all of surgical history to have the potential (even the probability in their judgment) for a 200 percent mortality." Though the child initially survived, he died later from complications.

Dr. Richard Jonas, later the chief of cardiac surgery at Children's Hospital, remembers working there with Dr. William Norwood, the first surgeon to operate successfully on a child with HLHS. "Bill came from the same school of cardiac surgery as Lillehei.... [They] encouraged surgeons to come up with any idea they could. For the good of many, a few individuals would have to be experimental subjects." He pauses and then says, "It was a paternalistic time."

Jonas gives one example from the 1980s. For a heart defect termed transposition of the great arteries, where the main arteries arising from the heart are backward, surgeons used to place artificial material inside the heart to redirect blood. Norwood and another surgeon decided to try something new: reverse the arteries themselves. The surgeons, Jonas later wrote, "performed the world's first successful neonatal arterial switch procedure without any fanfare and in front of an unsuspecting and subsequently astounded OR team, including myself."

Despite advances in the treatment of heart defects, HLHS confounded doctors for decades. The 1,000 babies born with it every year appeared healthy at delivery, but inexorably went into shock and died. No one thought they could be fixed. But in the late 1970s, Norwood devised a novel surgery to jury-rig the hearts. With the support of his chief of surgery at Children's, Norwood began operating.

Dr. Peter Lang, a cardiologist at Children's who helped Norwood develop the surgery, remembers being "accused of torturing babies." Most died, often after numerous surgeries and complications. Within his department, Lang estimates that only one-third of cardiologists favored the idea. Others believed the operations were "immoral and unethical," he says. "The early results were going to be terrible. I bent over backward to make sure parents knew it was unproven." Still, many parents proceeded. Among the survivors - precious few in the beginning - some children developed serious side-effects, such as strokes and other brain problems.

After a series of poor results - but with new knowledge from those cases - Norwood's procedure for HLHS was refined in the mid-1980s. Today, the treatment in most hospitals follows the principles laid out 20 years ago. Performed over a child's first years of life, three separate cardiac operations establish a circulation vaguely similar to that of a fish, whose heart has only one pumping chamber. In experienced centers like Children's Hospital, initial survival for children with HLHS is roughly 85 percent. But a fair number of survivors continue to develop heart-rhythm disturbances, disabling strokes, devastating digestive problems, and poor exercise tolerance. Not uncommonly, a parent leaves a career to care for the child, since months in the hospital are sometimes required. Nobody knows how long the jury-rigged heart will keep working; today, the oldest patient who's had the surgeries for HLHS is in his early 20s.

New knowledge relies on new experience. In pediatric cardiology, progress once depended on the first few families not being told - or understanding - what they were getting into. Was that still true for families like the Deffaas?

The afternoon she arrived in Boston in early November 2003, Jennifer Deffaa again lay on a gurney in a dark room and gazed at grainy images of her baby at around 23 weeks. Tworetzky, a fresh-faced cardiologist who had grown up in South Africa, confirmed the diagnosis. In his report, he wrote, "Heart disease will most likely progress to hypoplastic left heart syndrome at term." Tworetzky explained that the survival rates with surgery were an encouraging 85 percent but that the long-term prognosis was unknown. Then Tworetzky offered an incredible possibility: a chance at a complete cure, by fixing the heart in the womb. For fetuses with HLHS, the exit path for blood stops up like a clogged drain during early gestation, preventing normal heart growth. If the obstruction could be fixed early in the womb - in the same manner that adults get angioplasty, where a tiny balloon is inflated in a narrow vessel - maybe the heart could normalize. As Brian later told me, "It seemed so simple."

The notion wasn't new. According to one HLHS study, doctors attempted fetal angioplasty 12 times from 1989 to 1997. And it wasn't so simple. Four fetuses had died after a day, six babies died after delivery, and only two survived. Immediately after the experimental procedure, three women also required emergency cesarean sections, causing them "significant morbidity," or harm, according to the study, published in 2000 in the American Journal of Cardiology. The procedure worked in only one of the two surviving babies, and even then, the obstruction returned and had to be reopened several times after delivery.

Then, in 2001, one couple from the Boston area learned that their fetus, just over 20 weeks in the womb, had early signs of HLHS. They came to see the team at Children's Hospital, who thought previous fetal procedures were unsuccessful because they were done too late. The hospital ethics committee permitted the team to proceed. Eleven weeks later, Baby Jack was born without HLHS, a success that made the front page of The New York Times.

This success intrigued the Deffaas, but the risk to the mother worried Brian. "We could always have other kids," he tells me later, nodding to Jennifer, "but I only have one of her." To position the uterus for the procedure, an incision might be needed. Jennifer accepted the risk. "There was some risk to opening the abdomen up," she says, "but it would be similar to a C-section." The fetus had its own risks: Doctors would guide a tiny catheter into a blood vessel the size of angel hair pasta. As Brian explains, "One miss could damage [our baby] permanently. We've seen how fuzzy the ultrasound pictures could look."

Despite the coverage in national media, that case of Baby Jack still hadn't been evaluated and published in a scientific journal. And among the handful of similar attempts at Children's at the time, Baby Jack was the only child to be cured of HLHS by fetal intervention. Reassuringly, none of the mothers suffered complications. But taken together, the hospital's experience was anecdotal - that is to say, entirely unproven.

To the Deffaas, the fetal surgery was an up-front gamble. Brian said, "From my point of view, I'd rather have something bad happen now than 15 years from now." If it worked, their child might be cured. But if it didn't, they believed they would lose very little, since their baby would just get the standard operations later.

One week after the diagnosis in California, Jennifer was wheeled into an operating room at Brigham and Women's Hospital, which connects by a bridge to Children's. Doctors anesthetized her and temporarily paralyzed her fetus. A large team of specialists gathered.

Tworetzky later played a video of the procedure's ultrasound for me. He pointed to a long needle passing through Jennifer's belly and entering her uterus, as if for an amniocentesis. However, in this case, the obstetrician pushed the needle directly through the baby's chest and into the left ventricle of the heart. Into the hollow needle, Dr. James Lock, an interventional cardiologist, threaded a thin metal wire just thicker than a hair through the blockage in the heart. Then he floated a tiny, deflated balloon over the wire, so it straddled the blockage. Delicately, he then injected salt solution to inflate the balloon, which was raisin-sized, to pop open the obstruction.

Suddenly, blood began leaking from the fetus's heart. As the heartbeat slowed excessively, Tworetzky remembered, concern spread in the room. The doctors responded immediately. To relieve the accumulating pressure, doctors inserted another needle to drain the blood around the heart. Then they injected adrenaline directly into the fetus's heart - Pulp Fiction style - and the beating improved.

The entire procedure took a little more than an hour. Shortly after Jennifer regained consciousness, the ultrasound was repeated, and Tworetzky reported that the blockage seemed a little better. Jennifer was discharged soon afterward and the family went back to LA, where they stayed until shortly before the birth almost three months later.

I was on duty in the cardiac intensive care unit at Children's when the call came. The newborn unit said William Deffaa had just been born at Brigham and Women's, and the doctors there were rushing him over.

When they first learned of their fetus's diagnosis, the Deffaas had only days to mourn the loss of a normal child before deciding whether to sign a legal certification of "informed consent," allowing someone to put a needle into their baby's heart with the desperate wish that it might help. In truth, no one had experience to guide them. In the old days, doctors intentionally hid details about new therapies. But even modern doctors can only offer vague possibilities.

In situations like these, parents sometimes ask their physicians, "What would you do if this were your child?" Physicians almost never answer candidly. Doctors should keep their distance, goes the thinking, since they tend to push innovative therapies too much. Last year, for example, the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Delaware, fired Norwood, who had left Children's in 1984, for allegedly misleading parents when he modified a standard surgical procedure for HLHS. The hospital said the staffers involved "failed to comply with hospital policies regarding informed consent and the use of a medical device." (Norwood has disputed this.)

Some doctors still advocate experimental treatments on fetuses and children to benefit society instead of the first patients. These people think no parent should refuse therapies - even experimental ones - for cardiac diseases like HLHS. In a 1996 editorial in the journal Cardiology in the Young, an international group of pediatric cardiac specialists, including a few Americans, argued that all affected children should be operated on for the greater good: "The road to recovery and cure, if found for one patient, increases the hopes of others.... The clinician or researcher should never give up! ... The decision to be made by a pregnant mother carrying a malformed child should be a confrontation between her own needs, her own personal condition, and the needs of society."

Historically, regulations were created to stop ends-justify-the-means research. The notorious experiments of Nazi physicians, like human cold-water immersion, led to the creation in 1947 of the Nuremburg code, a series of principles to protect medical subjects. American researchers largely ignored them. For example, Sloan-Kettering's Dr. Chester Southam injected cancer cells into unsuspecting people in the early 1960s, researchers in Texas prescribed placebo birth control pills to unsuspecting women in 1971, and even Dr. Robert Cooke, who would later become a respected leader in bioethics, exposed orphaned children to heat stress early in his career to study dehydration.

In 1966, Dr. Henry Beecher of Harvard Medical School exposed scores of such unethical studies in a blockbuster article in the New England Journal of Medicine, and the same year, the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare mandated the use of "institutional review boards," or committees to protect human subjects. Even then, few hospitals took them seriously. But the public disclosure in 1972 of the infamous Tuskegee study of syphilis in African-American men led to passage of the so-called common rule, which mandates that all people must give "informed consent" to participate in research.

Today, many researchers argue that the pendulum has swung too far toward regulation. At a recent lecture at Children's Hospital, bioethicist Norman Fost outlined a typical scene when he participated in a meeting of the FDA's pediatric subcommittee last year. For an entire day, panelists discussed the ethics of a single research project in which healthy children would receive a single 10-milligram dose of dextroamphetamine - the pharmacological equivalent of less than five cups of coffee. Only a few decades ago, he said, patients were warned, "Don't be a guinea pig." Today, many people seeking potentially life-saving therapies are forced to demand, "How do I get in?" In the modern era, we're now seeing a curious situation where parents insist on innovative therapies, despite doctors' warnings.

The hope of success, however infinitesimal, can resonate powerfully. Perhaps parents latch onto fetal intervention like a life preserver. In speaking with several mothers who chose fetal angioplasty, I was astonished how quickly they'd made their decisions, regardless of fastidious informed-consent disclosures. The hours of intensive counseling were a coda to their gut reactions.

One mother who had the fetal surgery in 2003 tells me today, "We didn't have time to [expletive] around." Jennifer Deffaa says now, "We knew right away we wanted to do it." Baby Jack's mother, who wants to remain anonymous, worried over having an ill child and the subsequent marital stress and considered many options, including terminating her pregnancy. But when the fetal procedure was offered, she says, "Even with a 99.5 percent chance it wouldn't work, it was a very easy decision to make."

But what's interesting - and a further source of ethical consternation - is that many pediatric heart specialists today might themselves forgo even the standard post-birth surgeries for HLHS, leaving aside experimental fetal surgery. During a discussion at the 2001 symposium of the Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Society, for example, an audience member asked what each of the half-dozen prominent physicians on the panel would do if their own child were born with HLHS. According to two physicians in the audience that day, the majority chose a surprising option: letting the child die peacefully, with no surgery.

In 2003, a national survey of pediatric heart specialists published in the American Journal of Cardiology found that given a hypothetical prenatal diagnosis of HLHS, one-half would terminate pregnancy, and only one in five was confident of continuing pregnancy. If the baby was diagnosed after birth, one-third would choose a peaceful death, one-third didn't know what they'd do, and one-third would pick treatment. Interestingly, the panelists at the 2001 conference who would choose peaceful death for their own children were asked whether their hospitals offered this option. Almost to a person, they said no.

So on the one hand, pediatric cardiologists may offer, and in some cases encourage, invasive interventions. In many cases parents want it badly, too. But on the other hand, many doctors wouldn't take their own medicine.

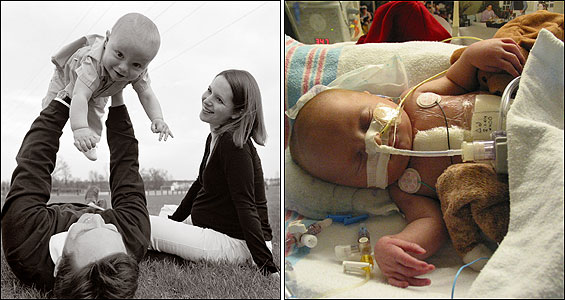

Born on January 22, 2004, and weighing 5 pounds 10 ounces, William Deffaa was an hour old when he arrived at Children's cardiac intensive care unit. A plastic tube in his throat connected to a breathing machine. We placed IVs in his veins, and I spoke with the attending physician. Brian Deffaa came to visit and taped a small picture of himself and Jennifer to William's warmer, orienting the picture so William might see it when he opened his eyes. Brian also placed a silver cross next to the ventilator.

But as it turned out, William wasn't cured like Baby Jack. William's left ventricle was too small to pump enough blood alone and yet wasn't small enough to be written off completely. The experimental procedure had created a heart that was tantalizingly, but not quite, normal.

Again, William's parents and physicians faced a critical choice. We all could act as though the fetal surgery had failed. If so, William would get the standard surgery that had an 85 percent survival rate and go home in a few weeks but have the long-term uncertainty of all kids with HLHS. Or the team could push ahead with more innovative but unproven strategies that might normalize the heart. Choosing innovative therapy is like loosening a jar's lid; the first twist is the hardest.

After much discussion, the Deffaas opted to gamble again to save William's left ventricle. So when he was 5 days old, William had his first open-heart surgery, in which a patch was placed in the heart to encourage the left ventricle to grow - another promising but unproven strategy.

After the surgery, William's chest was left open for two days until the swelling went down. Two weeks later, he had his second heart surgery and, after another 10 days, a third operation to fix a complication. Fluid kept flooding the space around William's lungs, so tubes were inserted into his chest. In addition, the baby had several procedures where balloons again were threaded into the heart to relieve blockages. He was on and off breathing machines. After the first two weeks, I had rotated into a different area of the hospital; William never left the unit for the first three months of his life.

One day, I walked through the unit and spied Brian and Jennifer reading a story out loud as they held the book in front of William's face, although the child was sedated and on a ventilator. The physician in me was skeptical, but the father in me was touched.

The Deffaas often questioned their decision and compared William's progress to other newborns with HLHS who got the standard surgery. Jennifer says, "We'd see kids that were technically physiologically sicker than Will, and they're going home in a few weeks, and we're there for months. Where's the right for us to put William through that?"

When William, almost 3 months old, was at long last stable enough for discharge, no one knew if his left ventricle would normalize. In Brian's words, William's procedure was "a marginal success with possible positive future implications." The baby's prognosis was far from clear.

Medical advances, like those in HLHS, are not easily won, but built on the backs of many children. Like the initial Allied soldiers storming Normandy, somebody has to go first. Perhaps for those on the front lines, denial is a necessary partner of hope.

A few weeks after William left the hospital in the spring of 2004, I flew to Maryland to meet the Deffaas in their new hometown (they now live in Michigan) to talk about their choices. Unfortunately, William had suffered an episode of low oxygen levels and had been admitted to Johns Hopkins. So I met Brian and Jennifer at a nearby restaurant, where, after four months, they were still glued to a cellphone that could summon them back to a hospital.

What made them sacrifice so much? I ask. "We worked so long for this baby," says Jennifer. "We loved him so much," even in the womb. Repeatedly, the Deffaas emphasize that the risks of fetal surgery were abundantly clear. Despite the complications, the Deffaas didn't regret their choice. "If William did pass away, I could live with myself since we did everything we could for him," Brian once said. The Deffaas are their child's most passionate advocates. Had the doctors gone too far? Absolutely not, Brian says. "You have the responsibility to push the envelope," he continues. "We came to Boston for that."

Maybe doctors of years past withheld information because they assumed no one would permit new therapies. But Brian and Jennifer's decisions show that medical progress needn't depend on deception. The Deffaas weren't in denial; their honest, well-worn hope for William just defied my frame of reference. It was an unusual role reversal. A physician, I was increasingly skeptical of the innovative therapy, while Brian and Jennifer seemingly harbored no regrets. I left dinner feeling inadequate; their reservoir of faith in medicine seemed much deeper than my own.

At home, William had trouble growing. Over the following months, he ate mostly through a tube that was surgically implanted into his stomach and frequently vomited. Taking care of William was tough. "It's a stress unlike any other," Jennifer says, "and it can be draining." The couple only occasionally got out for recreation. At night, says Jennifer, William "slept at the foot of our bed, and when he coughs, we shoot up instantly." Later, William had several problems requiring hospitalizations in Boston, and the couple stayed apart for long periods while Brian worked.

After months, William returned to Children's Hospital, and tests showed that the left ventricle hadn't grown and, while not entirely vestigial, still had an inadequate pumping capacity. Last summer, he finally got the standard surgery for children with HLHS.

In the end, if William had not had the fetal intervention or patch placed to encourage heart growth, he would have arrived at a similar point - and almost certainly with less suffering. Now almost 11/2, William initially had some developmental delays, but has progressed a great deal since his most recent surgery. He crawls and depends less on his feeding tube. His first word was "cat." He smiles responsively to his mother and father. And Brian - ever optimistic about William's future - tells me, "If he can get through this and keep smiling, we should be able to as well."

Remarkably, Brian still has faith that innovative therapy may cure his son one day. Children, he e-mails me, "have remarkable abilities to adapt and cope with limitations. Science and research can ... potentially provide a treatment for further growth and total reversal to a two-ventricle heart." The couple is expecting another son in July, and tests show no signs of heart trouble.

I ask the hardest question: Knowing where William stands now, would Brian choose the same path again? "Yes," he replies, his son "deserves every safe and reasonable attempt to help him. And so do the kids who will succeed him."

Darshak Sanghavi, a fellow in pediatric cardiology at Harvard

Medical School, writes a medical column for the Globe and is the author

of A Map of the Child: A Pediatrician's Tour of the Body. E-mail

sanghavi@post.harvard.edu. ![]()