back to article archive at www.darshaksanghavi.com

The Mother Lode of Pain

Some women insist on a drug-free childbirth - even though it might be agonizing - while others opt for a numbing epidural. Is this all part of the simmering debate between natural and modern medicine, or are some women embracing labor pain for a more heroic cause?

ON WEDNESDAY, APRIL 7, 1847, Dr. Nathan Keep made his way to the stately house at 105 Brattle Street in Cambridge. The vice president of the American Association of Dental Surgeons and the owner of a thriving dental practice, Dr. Keep had just that day published a seminal monograph on dental anesthesia in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, which would later become the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine. Now he planned to take his work one step further.

Overlooking the Charles River, the house had a history appropriate to Dr. Keep's radical purpose. Abandoned by supporters of the British monarchy in 1774, it served as General George Washington's headquarters during the siege of Boston in the winter of 1775. On the day of Keep's house call, the estate was occupied by the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his second wife, Frances "Fanny" Appleton, who was in labor with her third child.

|

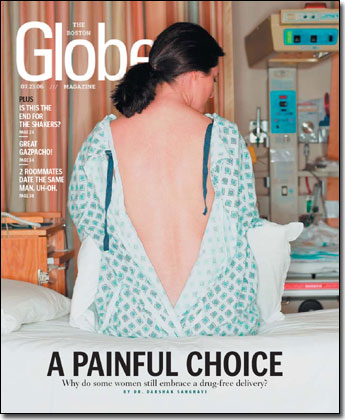

The anesthesiologist's epidural tool kit includes a flexible plastic catheter (bottom left). More than a third of women delivering at large hospitals nationwide forgo having an epidural. (Photo / Joel Benjamin) |

Fanny, a cosmopolitan woman who had traveled widely in Europe (where she met her husband), had not summoned Dr. Keep for his dental expertise. Less than four months earlier, Fanny learned, an English physician made history by giving ether anesthesia to a woman in labor. This breakthrough aroused great controversy, and no one in North America had followed suit. Despite their connections, Fanny and her husband were unable to find an obstetrician willing to administer anesthesia during childbirth. But Dr. Keep, who had given ether in hundreds of cases for dental surgery, consented to help Fanny.

Thus began the first obstetrical use of anesthesia in the United States: At what is today known as the Longfellow House, Fanny inhaled the ether mixture from a bong-like device of Dr. Keep's invention as a midwife tended to the delivery. According to Henry Longfellow's diary, "While under the influence of the vapor there was no loss of consciousness, but no pain. All ended happily." Fanny delivered a healthy girl, also named Fanny, and was so grateful for the anesthesia that she wrote to a friend, "[One] would like to have the bringer of such a blessing represented by some grand, lofty figure like Christ, the divine suppresser of spiritual suffering."

Six years later - also on April 7 - Queen Victoria received chloroform anesthesia for the birth of Prince Leopold (she later publicly approved of "that blessed chloroform").

Despite these extraordinary testimonials to the power of anesthesia, the control of pain during labor elicited powerful opposition. For millennia, humans had no effective means to control pain and thus created an elaborate web of sacred rituals and explanations for it. Pain was accepted as divinely mandated or spiritually transformative and therefore necessary. (As C.S. Lewis wrote, "All the great religions were first preached, and long practised, in a world without chloroform.")

What's fascinating is that now, although we have had the power to banish labor pain for more than a century, not all women can bring themselves to do so. Almost two-thirds of women delivering at large hospitals nationwide do receive epidural anesthesia (which numbs the lower part of the body), and the number is growing. But some shun all painkillers. At Boston-based Isis Maternity, which provides childbirth education for thousands of patients from area hospitals like Beth Israel Deaconess and Brigham and Women's, about 1 in 4 women choose natural childbirth classes over the more epidural-friendly "prepared childbirth" class, according to cofounder Johanna Myers McChesney.

Today we heatedly debate the right thing to do - embrace a natural, authentic approach or tap the miracles of science. In fact, much about childbirth and early motherhood sees a struggle between these two sides. This spring, a National Institutes of Health panel reported that a growing number of women who have no medical need for a caesarean are opting for the surgery, in some cases because they simply want to dictate when and how the baby arrives - news that was met with fear that vaginal births might fall out of favor. In May, Massachusetts's public health commissioner reversed a prohibition on hospital giveaways of infant formula, after months of fighting between supporters of breast-feeding and advocates of formula and a free market.

But is the shunning of obstetrical anesthesia about something more than natural versus modern? The vocal minority who purposely skip epidurals have created entirely new secular justifications for pain - especially during labor and childbirth - which are no less dogmatic than the earlier holy justifications. Why, even now, are people so unwilling to let go of pain?

POET SYLVIA PLATH once described labor as a "long, blind, doorless and windowless corridor of pain." The vaginal canal is so richly supplied with nerve endings and pain fibers that it's almost uniquely suited to create agony. In the first stage of labor, the cervix stretches open to almost 10 centimeters ("full dilation"), and the baby's head delivers from the uterus into the vaginal vault. In the later stages, the entire vaginal canal stretches open to pass the baby. According to well-studied pain questionnaires from the early 1980s, though a few women feel almost no pain, about two-thirds of women called their labor pain "severe" or "very severe" and most of the remainder rated their pain as "horrible."

Despite the initial endorsement of obstetrical anesthesia by women like Fanny Longfellow and Queen Victoria, many at that time considered pain to be biblically mandated and a necessary prerequisite for atonement. This thinking originates in Genesis 3:16, where God punishes Eve for eating from the Tree of Knowledge: "I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children." And many physicians opposed obstetrical anesthesia, believing that pain itself had transformative and healing power. In 1851, the British journal Lancet claimed that a woman's forceful screaming from pain during labor could, among other benefits, prevent vaginal tears.

But by the 1900s, some doctors began to rethink their position. Dr. Joseph De Lee, a Chicago obstetrician, was a leading early-20th-century advocate for medically managed childbirth. He ridiculed the notion that natural childbirth was best, since it frequently results in serious complications; De Lee even wondered "whether Nature did not deliberately intend women should be used up in the process of reproduction, in a manner analogous to that of the salmon, which dies after spawning." Pain aside, in the late 1800s, almost 3 to 7 percent of infants and 1 percent of mothers died in childbirth. In the first half of the 20th century, feminists saw childbirth as a battleground for human rights and advocated powerfully for better access to anesthesia and technologically advanced medical care, according to research from University of Florida-based historian and anesthesiologist Donald Caton. Within a few decades, infant and maternal deaths plummeted by 99 percent. By 1948, almost half of laboring women also received some form of obstetrical anesthesia in hospitals, where most delivered. This progress came at a price. Often for arbitrary reasons, hospitals barred fathers from delivery rooms and enforced separation of newborns from mothers, greatly increased the number of caesarean deliveries, and instituted seemingly impersonal policies. And thus a continuing counterrevolution, also initiated by feminists, began in the 1950s: the natural childbirth movement. It recast labor and delivery not as a divine punishment to be endured but a gift to be treasured without medical interference or anesthesia. Even Pope Pius XII stepped into the debate in 1956, saying Christian women could avail themselves of pain relief, but they shouldn't "use it with exaggerated haste."

To some extent, continuing frustration with modern childbirth is understandable. Many women today bemoan the cold efficiency of some obstetrical wards. And in 2004, Massachusetts recorded its highest caesarean delivery rate in its history, at almost 30 percent of all births. Clearly, some of these surgical procedures are preventable. For example, most hospitals place fetal heart monitors on healthy laboring women to detect possible fetal suffocation. This maneuver powerfully increases the chance of a C-section - and yet there is no convincing evidence this strategy reduces risks of brain damage or other complications.

But in rejecting medicalized childbirth - and considering anesthesia a part of that unnatural process - some women once again have embraced pain. And they also have given it a postmodern interpretation.

OVER LUNCH IN WORCESTER, I spoke with a colleague of mine, Dr. Mary Valliere, the chief of palliative care at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, about why some individuals refuse pain relief. As an adviser to other physicians, Valliere is involved in prescribing more narcotics and other analgesics to patients than almost any other doctor in the area. She also suffers from chronic neuropathic pain in her feet and hands, treated by a variety of medications. Valliere makes a surprising disclosure: She declined epidurals for all of her three pregnancies and had her first baby in a birthing center in 1981. "But I'm old," she says with a laugh. "Everyone was into natural childbirth back then." Still, "it didn't seem like it was pain that needed to be treated," she says, "since it was not pathologic." Valliere explains that pain doesn't always imply suffering, if the pain has purpose.

Birth "was definitely painful," she says. But "that's what the process is about. There's expectancy. It's joyful pain." The same isn't true, she says, about her neuropathic pains or the pain she once had with meningitis.

I later spoke with Jessie Ramey Zimmerman, a self-described "staunch feminist" and doctoral student in women's history at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, who tells the story of her great-great-grandmother, named Jessie Caldwell, who sailed from Scotland to the New World in 1880 and delivered a baby aboard the ship. "If she could do it in a boat," says Zimmerman, "why couldn't I also have a non-interventionist birth?" But when the time came for Zimmerman to deliver her first child in 2001, her obstetrician informed her that her 5-foot frame would not allow her 10-pound baby to pass. With "mixed feelings," Zimmerman consented to a caesarean section and named her son Caldwell after her ancestor. She says, "I felt like I hadn't actually given birth. This child had just been plucked from me."

For her second pregnancy in 2003, Zimmerman "wanted to feel that I had as much control over the process as possible." Though vaginal births after a previous caesarean delivery can have a slightly higher chance of causing a rupture of the uterus, Zimmerman decided that the risk was acceptable. When her insurance denied coverage to deliver in a birthing center, she hired a doula, or lay birth attendant, to accompany her at the hospital. Having "as close to a natural birth as possible," she says, "was a challenge to myself."

Labor was long. During that time, the doula helped with massages and brought towels and ice when Zimmerman was uncomfortable. It was, she says, "the worst pain of my entire existence." After four days, her cervix still hadn't budged from being only 4 centimeters dilated. "I was completely exhausted," Zimmerman remembers. Finally, she requested an epidural - and felt like a complete failure. "I was sobbing when I got it," she says. "There was a real element of disappointment." Her second son was born healthy that day. And although Zimmerman says she's unlikely to have more children, she has no doubt that she would try a natural childbirth again if possible.

I related Zimmerman's story to Ina May Gaskin, the legendary doyenne of midwifery who is widely credited with inspiring the home birth movement. Speaking from her Tennessee commune called "The Farm," Gaskin says she and her group have delivered thousands of babies with no anesthesia or other medical interventions from 1970 to 2000, and report referring out less then 2 percent of women for caesarean sections. Further, Gaskin says that only "about four or five" laboring women have ever needed transfer to a hospital to get any anesthesia.

Gaskin applauded Zimmerman's efforts to deliver without anesthesia but also praised her decision to accept the epidural when she thought it necessary. At least, says Gaskin, Zimmerman had the wonderful experience of attempting a natural birth.

Gaskin believes that all women have the potential for "ecstatic" births, a pleasure she was once denied. While giving birth for the first time in the mid-1960s, Gaskin recalls experiencing a sort of rapture with each contraction. "Pain is caused by muscular tension and fear," she says, and she'd controlled those impulses. Yet she was still talked into getting an epidural and had a forceps-assisted delivery "by a gang of masked attendants who came into the room and treated me like a ritual victim." She still recalls her nurse's "bony fingers" inside her vagina.

Today when Gaskin attends to deliveries, she says she becomes so attuned to her patients that she feels their pain and anticipates their physical needs, such as requiring a certain muscle massaged. And when childbirth "starts to hurt when things are happening, I tell them it's good."

Gaskin believes the nerve fibers that richly populate the birth canal can give pleasure as well as pain. In fact, she reports that about a quarter of her patients tell her they experienced the first or the most intense orgasm of their lives during childbirth. And here, at last, I understand Gaskin's modern justification for labor pain. In her opinion, women should experience the greatest pain of their lives in the hopes they might find the greatest pleasure.

It's an interesting secular variation on a religious narrative where unbearable pain suddenly transmutes to boundless joy - just as it is believed that the brutal crucifixion of Christ led to the opening of heaven's gates, or, for that matter, just as men blowing themselves to bits with suicide bombs think they will immediately appear in a paradise of virgins.

I present Gaskin with a hypothetical situation: What if she could give her patients a medicine that simply took away their labor pains but allowed them to remain at the Farm for their otherwise natural childbirths? Would she think that was a good thing?

"I don't think anybody would want it," she quickly answers.

INCREASINGLY, THE DATA suggest that Gaskin's patients are in the minority on this. According to a nationwide survey published in Anesthesiology last fall, the percentage of women getting epidurals at large hospitals tripled to about 60 percent over the past two decades, and the percentage of women receiving any sort of pain relief rose to about 90 percent. The same study suggests that many more women actually want better medical pain relief. It's easy to imagine that many forgo epidurals not because they want "ecstatic" births but because they fear side effects or their hospitals don't offer them.

During the procedure, a flexible, hair-thin plastic catheter is inserted into the mother's lower back - at a point several inches below the spinal cord and outside the structure bathing the cord in spinal fluid. Through the catheter, low doses of synthetic narcotics and local anesthetics travel directly to pain nerves near the spinal cord. The mother is numb only below her waist - the drugs don't course through her entire body and don't enter the baby.

Some hospitals also offer "patient-controlled epidural anesthesia," in which the mother electronically controls her own level of pain medication, and ultra-low-dose combined spinal-epidural (the so-called "walking epidural"), which lets many patients maintain sensation and muscle tone to push during labor.

Misconceptions about the safety and success of epidurals exist, and these deter some women from having the procedure. Earlier versions of epidurals did deliver higher doses of intravenous drugs, which caused excessive numbness, or used cruder equipment, but refinements have been made. Some people confuse epidurals with drugs that are "systemic," meaning they travel through the body and cross the placenta, affecting both the mother and child. And earlier studies, limited in size, did find problematic side effects with epidurals, like prolonged labor, which still attract publicity - yet current well-designed clinical trials undercut these findings. More than a dozen studies over two decades confirmed epidurals can prolong labor - but only for about 15 minutes, on average - and in some cases speed it up. In 2005, the New England Journal of Medicine reported that epidurals performed early in labor don't increase the risk for caesarean or forceps delivery or maternal fever. Major side effects are extremely uncommon; even mild ones like itching and slightly low blood pressure are easily treated. "Spinal headaches" became rare after the needles were redesigned in the 1980s. In 2002, the British Medical Journal reported no elevated risk of long-term back pain. Research consistently shows no impact on the baby's alertness at birth or breast-feeding rates.

When my wife, Elizabeth, went into labor at 2 a.m. with our first child in 2001, we lived in Gallup, New Mexico, where I worked as a pediatrician on the Navajo reservation. Like many couples, we'd attended a birthing class that warned of the side effects of obstetrical anesthesia, such as longer labors and worse breastfeeding rates, and these worried my wife.

Still, she knew she wanted some pain control. The hospital didn't offer epidurals at night, since we had no on-call anesthesiologist. According to the Anesthesiology study, small hospitals delivering fewer than 500 babies each year gave epidurals to half the percentage of women that larger hospitals did. The reason is that 80 percent of large hospitals have an in-house anesthesiologist who is immediately available to place an epidural. However, 95 percent of smaller hospitals must wake up and call one in from home, and 2 to 3 percent (like the Navajo hospital) have nobody at all. So at many hospitals, epidurals simply are unavailable in a timely fashion, if at all.

Thankfully, my wife didn't suffer. A few weeks before, I'd seen a kindergartner in the emergency room for severe belly pain. The surgeons wanted to operate for possible appendicitis; luckily I found bite marks on the boy and diagnosed a black widow spider bite as the pain's real cause. No operation occurred. It turned out the boy's father was a nurse anesthetist, who gave me his telephone number and gratefully offered to come in anytime for my wife's delivery, and I took him up on his offer.

Not everyone is so lucky. According to the Anesthesiology study, almost one-third of laboring women who want pain control today get poor substitutes for epidurals: systemic drugs like Demerol or Stadol that can make the mother sleepy and nauseous, affect the newborn, and not stop labor pain well. Additionally, most hospitals still don't offer cutting-edge walking epidurals and patient-controlled epidurals.

The nationwide lack of appropriate access to obstetrical anesthesia has a curious effect on prenatal education. Because many hospitals don't offer state-of-the art epidurals by round-the-clock in-house obstetrical anesthesiologists, they have no incentive to educate patients. So many parents-to-be attend prenatal classes of the Lamaze or Bradley variety that teach that breathing and relaxation methods are all that's usually needed and that frequently misinform mothers about modern anesthesia. Lamaze International's website, for example, asks women to "give birth without routine interventions" and warns of increased risk of fever, caesarean delivery, and fetal distress with epidurals. But according to Dr. William Camann, chief of obstetrical anesthesia at Brigham and Women's Hospital and coauthor of Easy Labor: Every Woman's Guide to Choosing Less Pain and More Joy During Childbirth, "The fact is that labor really hurts," and natural childbirth classes often "set up women for failure."

As a pediatrician, I have been present at hundreds of births and spoken with dozens of women who passed up anesthesia during labor. One justification I've often heard is that labor pain "empowers" women or gives them a sense of "control." But many women accept pain for a more mundane reason: They are poorly educated about obstetrical anesthesia and don't have access to compassionate and technologically advanced medical care. In that sense, Fanny Longfellow's story is especially relevant; she overcame both ignorance about anesthesia (by teaching herself about ether) and the lack of access (by finding a willing dentist when no obstetrician would tend her). She didn't rationalize the existence of labor pain.

STILL, THERE WILL ALWAYS be people who want their pain. When I was a teenager in New Jersey, I endured an optional religious challenge called the atthai, an Indian Jain custom of fasting for eight straight days. The idea is that the people should dissociate from the material world, even from something as elemental as food. Accomplishing the painful challenge is something of an ego rush; the hunger artists are honored as members of a holy community. (I look back on this now with agnostic disbelief.)

Like prolonged fasting, enduring labor without anesthesia attracts

notice. It casts the mother as a struggling heroine who - by sheer mental

force - gracefully keeps her body under control. "Natural childbirth

purists," author Margaret Talbot wrote in the

In this setting, the pain of unmedicated labor offers up a formidable, if artificial, trial that precedes entry into a highly selective sorority. It creates drama. It captures attention.

Yet pain in the end is an utterly primitive thing, a vestige of insect and reptilian brains. It evolved primarily as a way to change behavior without need for thought - to force one's hand to pull away from fire or tend urgently to an injured limb. Thinking beings, in some sense, have evolved beyond pain. (Some pain reflexes continue even in brain-dead individuals.) If anything, reliance on pain to create meaning during childbirth indicates a constricted imagination. Surely there must be more innovative challenges than voluntarily refusing effective, safe, and available pain relief during labor. As the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology states, "There is no other circumstance where it is considered acceptable for a person to experience untreated severe pain, amenable to safe intervention, while under a physician's care."

Which is why choosing to feel pain during childbirth strikes me as odd. Eliminating pain won't create a sudden existential crisis among mothers, because parenting is too rich an experience. And after all, being born is ultimately the least distinguishing feature of being human; everyone's done it and, moreover, no one remembers it.

Dr. Darshak Sanghavi, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the

University of Massachusetts Medical School and the author of A Map of

the Child: A Pediatrician's Tour of the Body. E-mail him at sanghavi@post.harvard.edu. ![]()