Parents often think their children grow up too quickly, but few are prepared for the problem that Dr. Michael Dedekian and his colleagues at the University of Massachusetts Medical School reported recently.

At the annual Pediatric Academic Society meeting in May in San Francisco, they presented a report that described how a preschool-age girl, and then her kindergarten-age brother, mysteriously began growing pubic hair. These cases were not isolated; in 2004, pediatric endocrinologists from San Diego reported a similar cluster of five children.

It turns out that there have been clusters of cases in which children have prematurely developed signs of puberty, outbreaks similar to epidemics of influenza or environmental poisonings. In 1979, the medical journal The Lancet described an outbreak of breast enlargement among hundreds of Italian schoolchildren, probably caused by estrogen contamination of beef and poultry. Similar epidemics in Puerto Rico and Haiti were tracked by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the 1980’s.

Increasingly — though the science is still far from definitive and the precise number of such cases is highly speculative — some physicians worry that children are at higher risk of early puberty as a result of the increasing prevalence of certain drugs, cosmetics and environmental contaminants, called “endocrine disruptors,” that can cause breast growth, pubic hair development and other symptoms of puberty.

Most commonly, outbreaks of puberty in children are traced to accidental drug exposures from products that are used incorrectly.

Dr. Dedekian’s first patient was evaluated for possible genetic endocrine problems and a rare brain tumor before the cause of her puberty was discovered. It turned out that her testosterone level was almost 100 times normal, in the range of an adult man. The same problem affected her brother.

The doctors realized that the girl’s father was using a concentrated testosterone skin cream bought from an Internet compounding pharmacy for cosmetic and sexual performance purposes. From normal skin contact with their father, the children absorbed the testosterone, which caused pubic hair growth and genital enlargement. The boy, in particular, also developed some aggressive behavior problems.

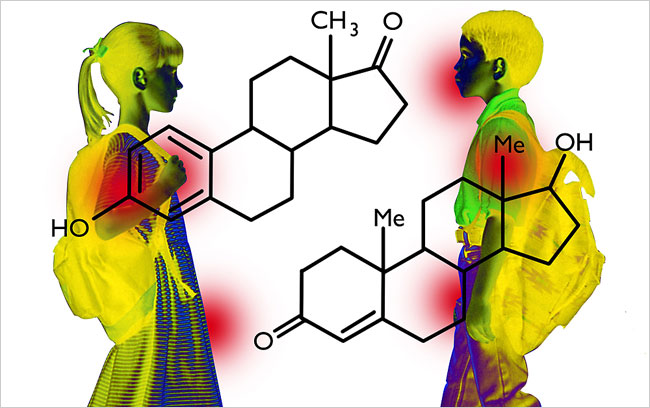

Sex hormones are potent because they are easily absorbed through the skin and resist degradation better than many other hormones. Unlike protein-based hormones like insulin, sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen are technically steroids, meaning they are derived from cholesterol.

Primarily made by the liver, cholesterol begins with tiny pieces of sugar that are joined, twisted and oxidized in a dizzying series to make an end product that resembles the interlinked rings of the Olympic emblem. Dr. Joseph L. Goldstein, Nobel Laureate and a biochemist in Texas, once called it “the most highly decorated small molecule in biology,” because 13 Nobel Prizes have been awarded for its study.

Through further processing, primarily in the gonads and adrenal glands, cholesterol is converted into sex hormones like estrogen and testosterone. Kenneth Lee Jones, the former chief of pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, noted pediatric cases similar to those described by Dr. Dedekian in a 2004 report in the journal Pediatrics.

At that time, unregulated “prohormones” like Andro, famously used by Mark McGwire, the former St. Louis Cardinals power hitter, and banned by federal law in 2005, were available as topical sprays used to enhance libido. Dr. Jones said the sprays used by adults in some households permeated the children’s bedsheets, and the early puberty stopped only when the adults stopped using the sprays and also discarded old sheets.

Testosterone-containing products are not the only trigger of disordered puberty in children.

In a 1998 paper in the journal Clinical Pediatrics, Dr. Chandra Tiwary, the former chief of pediatric endocrinology at Brook Army Medical Center in Texas, reported an outbreak of early breast development in four young African-American girls who used shampoos that contained estrogen and placental extract. The early puberty reversed once the shampoo was stopped.

In the tradition of previous physicians who deliberately exposed themselves to possible pathogens, Dr. Tiwary tried the shampoos on himself. He carefully measured his own levels of various male and female sex hormones to establish his baseline, used the shampoos for a few days, then repeated the tests.

While Dr. Tiwary is quick to admit that his unpublished findings must be interpreted with great caution, some of his sex hormone levels changed by almost 40 percent after he used the shampoos. In some cases, substances other than sex steroids may also disrupt normal sexual development. In Boston at the annual Endocrine Society meeting in June, Clifford Bloch of the University of Colorado School of Medicine presented several cases of young men who had developed marked breast enlargement from using shampoos containing lavender and tea tree oils, which are widely used essential oil additives that present no problem for adults. (Unlike Dr. Dedekian’s cases, these cases were not a result of passive transfer from parents. The boys themselves used the shampoos.)

Dr. Bloch collaborated with scientists at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences in North Carolina to test the oils on human breast cells grown in test tubes. Lavender and tea tree oil had the same effect on the cells as estrogen.

Dr. Bloch speculates that the findings, which he is submitting for publication in a peer-reviewed journal, may explain the boys’ breast growth. He noted, however, that cells in a test tube are a far cry from humans, so the relationship of the essential oil to breast growth remains hypothetical.

While pediatric endocrinologists have implicated pharmaceutical or personal care products for causing pubertal problems in children, some environmental scientists also claim that some widespread industrial and pharmaceutical pollutants harm the normal sexual development of fish and animals. By extension, they may also contribute to earlier or disrupted puberty in children, these scientists contend. Robert Havelock, a senior reproductive toxicologist at the Environmental Protection Agency, said these concerns “caused a shift in worry from cancer to noncancer” effects of environmental pollution over the past decade.

In 1994, scientists found that estrogen-like chemicals from plastics manufacturing plants that had contaminated sewers in England caused genetically male fish to develop into females. In the early 1980’s, major spills of the DDT-like pesticide dicofol in Florida led to the “feminization” of the reproductive tracts of male alligators.

Robert Cooper, the chief of endocrinology at the reproductive toxicology division of the Environmental Protection Agency, says various sources of endocrine disruptors, like manufacturing chemicals, may be leaching into the environment. While their relation to pubertal problems in children remains highly speculative, he believes further study is needed.

Past epidemiological evidence, however, does worry Dr. Cooper, because some chemical exposures have been associated with early puberty. In 1973, thousands of Michigan residents ate food contaminated by a flame retardant, PBB, which was later correlated with earlier menstruation in girls. In Puerto Rico, which has some of the world’s highest rates of early puberty, the condition was linked to higher levels of a plasticizer called phthalate in affected children.

Governmental efforts to create a systematic method to assess possible endocrine disruptors from environmental sources have stalled.

In 1996, Congress directed the E.P.A. to develop a comprehensive screening program for possible endocrine disruptors within three years. Dr. Cooper says no such program has begun operation, a failure he attributed largely to stonewalling by chemical industry representatives who serve on an advisory committee for the program. Now the proposed rollout is December 2007, but Dr. Cooper said, “They may be dreaming.” Critics cite the program’s high potential costs and lack of reliable laboratory tests.

Protecting children from endocrine disrupters in cosmetics and prescription drugs may also be difficult in the near future.

In 1989, the Food and Drug Administration proposed allowing up to 10,000 units of estrogen per ounce of cosmetic, the approximate oral daily dose of hormone replacement therapy for postmenopausal women. Dr. Tiwary said that in the early 1990’s he filed an adverse drug report with the agency about hormone-containing shampoos but that to his knowledge, it never came to anything.

Reached by e-mail, a spokeswoman for the F.D.A. said that the agency was “aware of some reports describing premature sexual development” with shampoos but that it had concluded that “there is no reason for consumers to be concerned.”

At this time, “placental materials are neither prohibited by cosmetic regulations nor restricted” by the F.D.A., she wrote.

Dr. Dedekian said that while prohormones like Andro are no longer commercially available, lax regulation of so-called compounding pharmacies allows the manufacture and sale of concentrated testosterone creams, like the one affecting his patient, without government oversight.

Topical lotions and creams containing testosterone may become more common. In 2000, Solvay Pharmaceuticals secured F.D.A. approval for Androgel, a lotion to treat a syndrome the company calls low T, referring to low testosterone. According to the company’s Web site, the condition affects 13 million men over 45. From 2000 to 2004, the number of testosterone prescriptions doubled to over 2.4 million a year.

Solvay Pharmaceuticals referred questions on Androgel’s possible risks to Natan Bar-Chama, an associate professor of urology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

Dr. Bar-Chama acknowledged the theoretical risks of transfer of the hormone through skin contact with children, but he said he had never seen a case among the hundreds of men he has treated. He added, however, that it was prudent to take precautions when using the product, including hand-washing after handling the gel and wearing clothing to avoid skin-to-skin contact with others.

In 2003, an Institute of Medicine report stated, “There has been increasing concern about the increase in the number of men using testosterone and the lack of scientific data on the benefits and risks of this therapy.”

Dr. Dan Blazer, a psychiatrist at Duke who was chairman of the committee, said, “In no way did we find a condition that we defined as low T.”

The major clinical trial of Androgel’s effectiveness for low T, published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism in 2000, included neither a placebo group (patients who received an inactive dummy lotion) nor a control group (patients who did not have low T) for comparison.

Dr. Ronald Swerdloff, the chief of endocrinology at Harbor-U.C.L.A. Medical Center in Torrance, Calif., and a consultant for Solvay, who ran the study, said the trial was limited in scope since it examined “a new route of administration for an already established drug.”